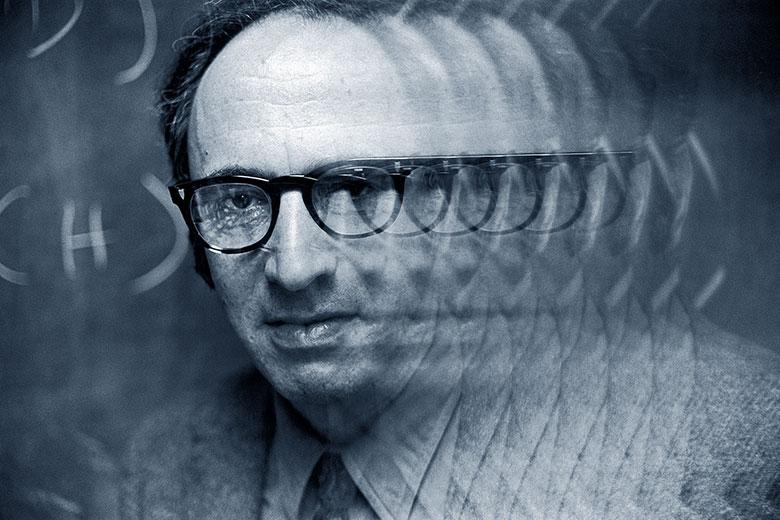

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 535-475 BCE), is sometimes known as the 'Father of Dialectics'. Many principles of interconnection and dialectics have some of their earliest known origin in his thought.

"You cannot step into the same river twice."

He's talking about the constant state of flux everything is in. Nothing is ever being, only a constant state of becoming. You cannot enter the same river twice, not because something happens to the river, but because the exact configuration of simpler elements which make up the river no longer exist. Instead, the river is now composed of a slightly different configuration of those simpler elements. Maybe a few drops less, but maybe a few different drops added in the meantime.

He saw the world as structured by logos, which served as a universalizing principle. It sees everything as existing in tension with its opposite, and these opposites inherently define each other: day and night, hot and cold, war and peace. You can't understand or conceptualize one without the other.

"Cold things warm up, the hot cools off, wet becomes dry, dry becomes wet"

This constant tension and opposition is actually what creates harmony and structure in our universe, rather than chaos. When plucking a string on a Lyre, or pulling back the string on a bow, the opposing forces, such as between the string and the bending bow string produce something both functional and beautiful.

From this, the conclusion is that everything in our universe is interconnected through constant transformation and mutual definition. Nothing can exist in isolation. Change is the only constant.

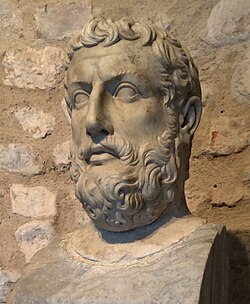

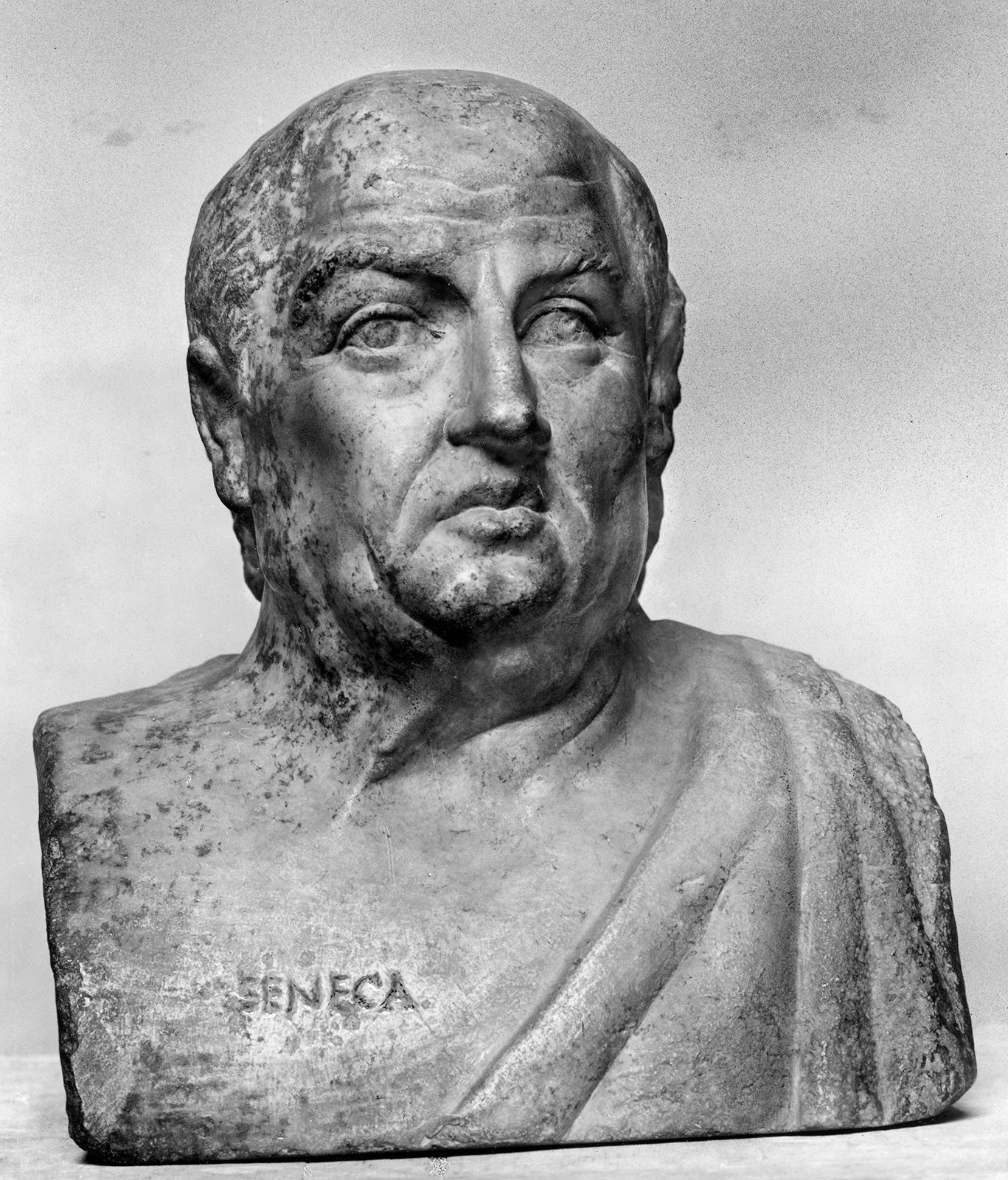

Seneca the Younger

Seneca believed that all humans are fundamentally connected as members of a shared "world-city". He said that we humans function like the "limbs of a great body", together making up a greater organism. He inspired an English poet centuries later named John Donne, who was inspired to proclaim "no man is an island". Just as a hand cannot flourish severed from the body, a person cannot truly thrive in isolation from the rest of humanity.

"We are members of one great body, planted by nature... We must consider that we were born for the good of the whole."

Seneca saw the cosmos as a single, living, material entity, which he called a "great animal" permeated by divine reason (Logos). He specifically emphasized sympatheia, the stoic concept that all parts of the universe are bound together in mutual influence. The stars, the seasons, human affairs-everything participates in a single rational order, the logos that permeates everything. What happens in one part of the whole ripples throughout the rest.

"We are waves of the same sea, leaves of the same tree, flowers of the same garden."

In addition to the philosophical conclusions of his physical monism, the social conclusions extended from his philosophy were quite cosmopolitan, and he saw national boundaries and social hierarchies as, in the richest sense, artificial. Our true citizenship is in the the world-city of all rational beings. We exist within a living network of inherent mutual dependence and influence.

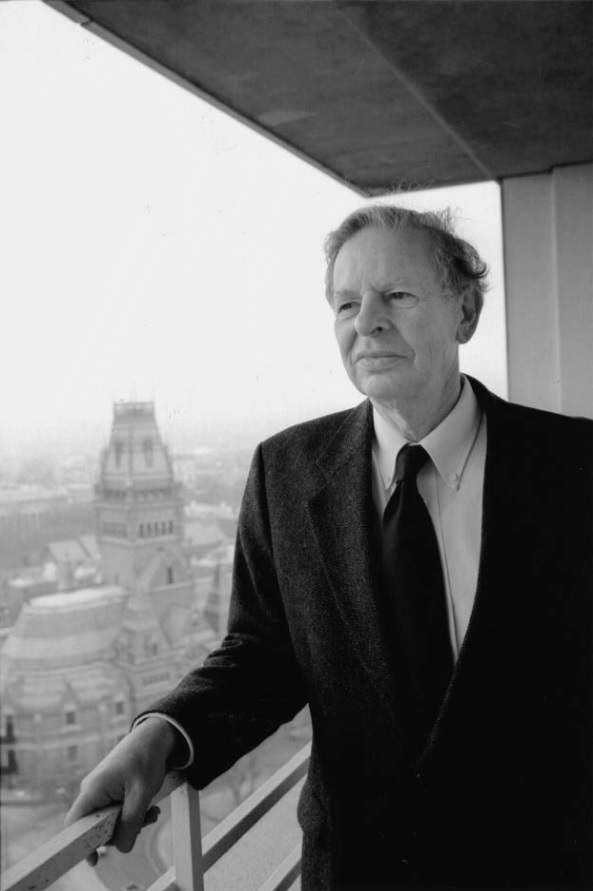

Lieberson's Evolutionary Epistomology

Social scientists have historically drawn from the playbooks of other disciplines, especially the hard sciences, rather than building their own epistimological models for analysis and understanding. For a long time, social scientists have used methods from hard sciences such as isolating your variables, controlling for confounds, making predictions and so on. This is a good epistomological model for predicting the motion of pool balls and planets, but many social scientists are coming to understand that this terse and rigid method of analysis isn't great for analyzing human society and people. These methods aren't suited for the messy, recursive and highly contextual nature of human social life. In his work "Barking Up the Wrong Tree", Stanley Lieberson argues for a model of anaylsis based on the work of Charles Darwin and discusses how his methods faced strikingly similar challenges in establishing rigor.

Lieberson argues that sociology has inappropriately borrowed its techniques and methodology from the paradigm set by classical physics. He argues that simple 'cause and effect' are ill suited for studying complex systems and due to that category error, can lead to cases of false causation and general incorrect conclusions. Most interestingly, he proposed utilizing an epistolary framework set by Charles Darwin in his study of evolution by natural selection. Darwin faced similar challenges with acceptance by the scientific community as many social scientists do now.

Lieberson saw many issues faced by Darwin as very similar to the issues social scientists face now. These included the need to draw rigorous conclusions from non-experimental observational data, the lack of prediction as a core standard for success, and the ability to work with an incomplete theory.

Lieberson also talks about a tolerance for incompleteness of a theory, allowing your theory to endure and become developed by others overtime. Not only allowing this, but emphasizing this dynamic, allowing your theory of evolution to take on an evolutionary character of its own! Lieberson views theory as an active process of knowledge making, a living corpus that is modified and expanded on and critically evaluated over time, which they view makes the theory successful, rather than a failure, as the classical physics model might suggest.

Furthermore, there is a decreased emphasis on prediction. Just because natural selection can't predict what new animals will evolve in 4 million years, does not make it worthless. Explaining the past and present are valid scientific goals as much as prediction, and it can help us discover more abstract, underlying forces at work within the complex system. You have to understand there is more than just direct causation in the world, there is also underlying causation, and confusing the two leads to all sorts of misunderstandings and contradictions. Within systems such as social systems, causality is both asymmetric and non reversible.

Even with a change in X that causes a change in Y, a reversal of X does not necessarily cause a reversal of Y.

Hubert Blalock's challenge to the criticisms of purely causal modeling left me pretty underwhelmed. He blames the issues with causal modeling on the practitioner's user error, which does have some merit to it, however, I strongly disagree with his conclusion that "There is no reasonable alternative to developing the 'much more complex causal models' required to study social phenomena". Instead of re-evaluating the tools we are using, he instead suggests we use these tools to create more complexity and variables to regression style models, rather than exploring new ways to evaluate these systems and phenomena.

This approach can lead be a slippery slope where one must constantly "control" for more variables in a futile attempt to simulate a true experiment, a goal derived from the physics model, but one that is ill suited for dynamic sorts of systems. Even in complex systems science, beginning to take its form in university's across the world over the past half a decade has started to adopt these types of methodologies. Rather than trying to account for infinite possible variables, it is far more fruitful to attempt to identify specific mechanics and forces at work within the system. Darwin was successful for simplifying the problem in this way, using tools like natural selection, genetic drift, migration and bottleneck and their emergent combination to explain phenomena. We aren’t bothered by if a mechanism is always relevant to a specific case, but as generalized forms.

I think that trying to find new techniques that are specifically relevant for sciences that are observing dynamic systems, such as ecosystems, weather systems, human society and beyond, is highly important. Being able to understand social laws as shifting, and being able to understand our work as researchers in the context of a dynamic, ever-shifting science, is incredibly important to maintaining good practice.

I have thought many times before about how Darwin's view of a dynamic science, where one form changes into another, dependent on its environment, with elements of the old, remaining in the new, and how that can be applied to many areas of science, especially social science, and on a philosophical level, perhaps as a fundamental principle of reality. If nothing else, understanding phenomena in this way is an important addition to our tool-belt as scientists and researchers.

Reading through this work has given me another interesting observation. Evolution operates with neither unique historical events reflecting unique historical causes nor a crass mechanical approach that evaluates a mechanism by how often it operates or how much of the variance it accounts for. A mechanism is still pertinent regardless of how often it operates to generate changes in the survival of a species or a species’ growth or decline in numbers. The mechanism is not evaluated in terms of the variance, but rather, it serves to provide explanation.

Kuhn and Paradigm Shifts

Thomas Kuhn was a highly influential philosopher of science, and as many of his contemporaries did, and as those who have come after have increasingly focused on, Kuhn talked a lot about perspective, relativity and the general tendency for science to take on a dynamic, rather than static character.

Kuhn highlighted that science tends to oscillate back and forth between two different stages of scientific development. These two phases are known as "normal science" and "paradigm shifts".

"Normal" science is what Kuhn refers to as our standard, business-as-usual type of science, which is based upon one or more concrete, past scientific achievements. The goal in this phase is to articulate and refine the existing scientific paradigm, rather than replacing it with a new one. During this phase, there's a lot of what he calls "puzzle solving", where the existing paradigm offers challenges which guarantee a solution.

Under every paradigm, there are a certain set of rules, assumptions and social constructs that exist, which govern how research is motivated. Every paradigm judges whether something is worth investigating, whether the tools and measurements being measured are valid and provides standards for what acceptable results even look like.

Paradigm Shifts represent large qualitative leaps in our scientific understanding. This conceptualization challenges the previously static and metaphysical understand of science, which viewed the process more as a constant state of refining the same ideas and epistemological frameworks. Rather than refining an old mode of thought, rather, a new mode of thought entirely is born. Different paradigms are so different typically, the results of the observations of each can't be directly compared, as the philosophical underpinnings of what is being looked for and how it's being interpreted, towards what ends, can all be radically different.

Very importantly, Kuhn also highlights how paramount or social context (paradigm) is. A new paradigm cannot become a new paradigm, no matter how logically or empirically correct it might be, if the cultural superstructure for one reason or another will not accept it. Try being a man of science during the Salem Witch Trials, as an example. He also points out that the current paradigm shapes how we as scientists think and understand, since the current paradigm is by definition our baseline we are starting at.

He also highlights a couple of secondary phases which lie as transitory states between these two primary phases. The pre-paradigmic phase is a chaotic phase in which there is no universally agree on best approach yet, and its a bit of a wild west of testing and debate, lacking a lot of systematic work, lacking a real structure. We also have the periods of crisis that emerge when enough anomalies that the current paradigm cannot explain accumulate and through this crisis, a new revolutionary paradigm can occur.

The world we live in is highly dynamic and constantly changing, so I think Kuhn's focus on dynamicism in science makes his work definitely the most interesting and resonant with myself and my understanding of science and the world. It reminds me of the Foucauldian discourse of truth we discussed a couple of weeks ago, and emphasizing that understanding truth is a dynamic social process, and building that expectation into our methodology is very important.